Before reading on check out the first two posts in this series:

Back in the day, I spent a lot of Friday nights at high school football games because my oldest daughter was a cheerleader. At the time, I didn’t really understand the game, so I stayed busy watching the cheerleaders, listening to the band, and taking in the crowd. There was always a lot happening, and honestly, it all felt equally important to generate excitement and hype the players up!

Over time, though, I started paying more attention to what was happening on the field. I noticed that the same plays kept showing up. I couldn’t tell you what those plays were called, but I knew they worked. I’m drawn to patterns. I find them. Week after week, the same patterns showed up, and week after week, they led to wins.

Late-Lee, that’s had me thinking about leadership and how we respond when the data starts telling us a lot at once.

When leaders analyze data well, it almost always reveals more than one thing. Strengths, gaps, inconsistencies, and opportunities can overwhelm even the best teams. And when everything shows up at once, the natural response is to try to address each and every single thing. New initiatives get added, new strategies get named and expectations begin to stack up. Before long, leaders are managing too many things at once, and teachers feel like they’re carrying far more than they can reasonably hold. The weight of it all is visible and undeniable.

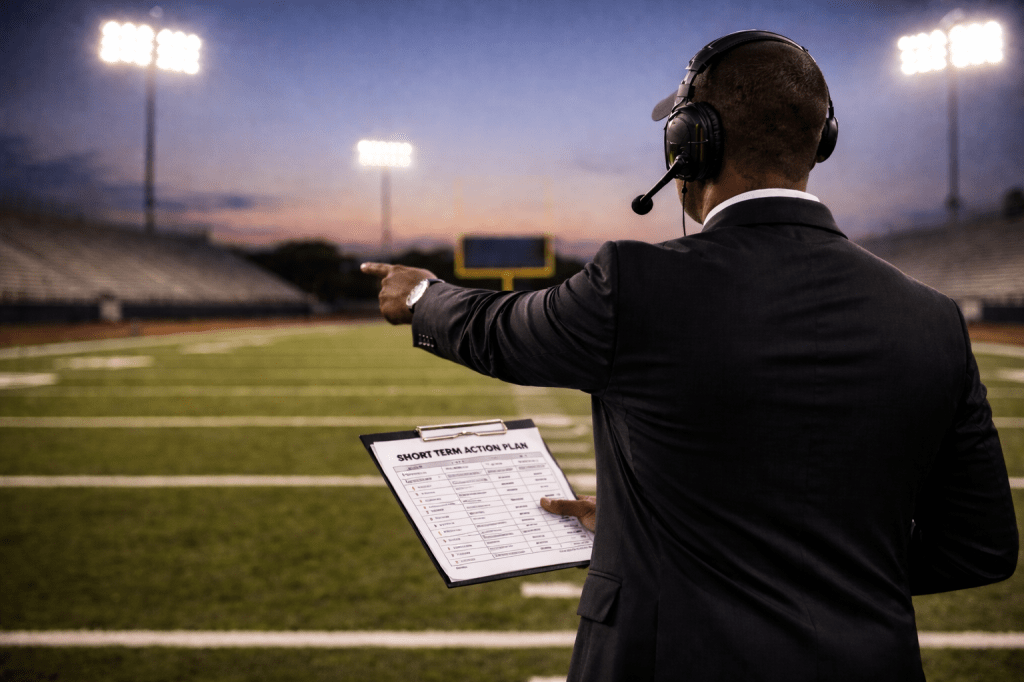

But just because the data reveals many things doesn’t mean we should act on everything it shows us. High-performing teams don’t rewrite the entire playbook at halftime. They make a few intentional adjustments and commit to running those plays well. The focus isn’t on calling more plays; it’s on choosing the ones that will have the most significant impact.

In schools, that matters because student achievement has to stay at the heart of every decision we make. Activity alone doesn’t move outcomes, but impact does. And the truth most leaders learn, usually the hard way, is that adult behaviors are often the most challenging part of the work. When we introduce too many initiatives at once, even well-intended ones, the job starts to feel heavy fast. Focus gets diluted, implementation weakens, and before long, the outcomes we’re hoping to improve begin to stall.

Adjusting the game plan means being disciplined about what we choose to change. It means identifying high-leverage actions that influence multiple outcomes simultaneously and being willing to let other things wait. Sometimes that requires saying “not yet” to good ideas so the most important ones have room to take hold.

Focused adjustments also honor the reality of teaching. Teachers don’t need a new play every week. They need clarity, consistency, and support to execute the plays that matter well. When leaders keep the game plan tight, teachers aren’t juggling a dozen initiatives at once; they’re refining their practice and building confidence in what they are doing.

That’s where training and coaching really matter. The goal is for the plays we call to become so familiar that they feel like muscle memory. Clear expectations, practiced consistently over time, allow teachers to focus less on what they’re supposed to do and more on how well they’re doing it. When that happens, instruction becomes stronger and more consistent, and students benefit from that stability.

Adjusting the game plan isn’t about doing less because the work is easy. It’s about doing less because the work is essential, and because doing too much often keeps the right work from ever fully taking root.

Before the second half moves forward, there’s a question leaders need to sit with:

Which one or two adjustments will have the most significant impact on student learning, and how will we support our teachers in implementing them effectively?

That’s where disciplined halftime leadership shows up.

Leave a comment